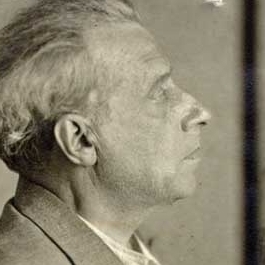

Bertolt Brecht was a major reformer of several aspects of 20th century theatre. He created an acting process, theories of dramaturgy and performance, a performance style, and wrote hundreds of plays and poems, many informed by his strong belief in Marxism. His later plays such as The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1954) and Mother Courage (1949) presented dilemmas for the audience to consider, putting the onus on the spectator to question and evaluate potential means to make redress for the characters’ plights. Brecht demanded a critical response from the spectator, an active intellectual engagement which he found lacking in the closed cycle of naturalism.

Brecht wanted to break down the ‘fourth wall’ through various devices: revealing decisions his characters made and the context in which they did so; making narrative techniques overt; and exposing the processes by which performances are constructed, even showing the actor to be aware onstage of the artifice of his or her role. These notions of public participation in change and an emphasis on process rather than product are fundamental to Brecht’s aesthetic vision.

Brecht was aware of the increasing danger of his position as a Marxist and public figure and so fled Germany in 1933. He left Europe in 1941 and went into exile in North America. He continued to write there, including a first draft of The Caucasian Chalk Circle and The Life of Galileo in 1947, the year when he was famously questioned about his Communist connections by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. He returned to a Communist East Germany in 1948 and a year later, with his wife, Helene Weigel, founded the still-extant Berliner Ensemble. Under his charge this became one of the most influential theatre groups in Europe, contributing to the politicization of writers and theatre artists worldwide.

Of all Brecht’s theatrical strategies, the most widely known is alienation, or the Verfremsdungseffekt. This alludes primarily to the critical perspective with which an audience should engage with the production as well as the attitude an actor might have towards his or her role. It was inspired in part by the non-illusionistic nature of Chinese theatre and especially Beijing Opera, to which Brecht was introduced when he met the actor Mei Lan Fang (1894–1961) in 1935 in Moscow. The Verfremsdungseffekt was made possible by many techniques, most notablyGestus. Actors should recognise a play’s keyGestus, or those actions which have social-political implications. Such awareness should help make visible the central dilemma of any one moment within a production. An example is Helene Weigel’s silent scream inMother Couragewhen she hears of her son’s death but must hide her response for her own safety.

Brecht differentiated between his Epic Theatre and naturalism’s Dramatic Theatre. Epic Theatre relies on narrative rather than plot, the action unfolding in self-contained scenes that make up the total story, each of which might be introduced by a slogan or a sign. It depicts social and political processes, whereas naturalism shows people governed by natural laws. From the RCTP

**EXCLUSIVE NEW FEATURE** Find out more about Bertolt Brecht via an RPA partner journal