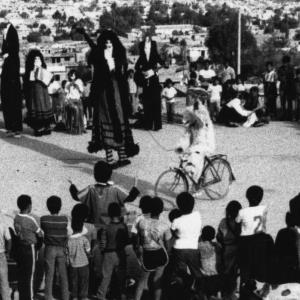

Pioneered by a trans-European group of artists, Dada is an ‘anti-art’ form that came into being in 1916, partly as a deliberately illogical response to the perceived irrationality of the First World War. Hugo Ball opened the Dadaist Cabaret Voltaire in a Zurich nightclub in February 1916. The Cabaret exhibited paintings, graphic artworks, and presented performances. These initially resembled conventional cabaret, staging poetry readings alongside musical turns. However, they quickly became much more experimental, combining dances and skits performed in masks; cubist costumes; recitations of manifestos; music exploring silence, rhythm, noise and sounds produced by the body; and unconventional poetry readings, emphasizing sound rather than literal meaning – combining drumming and bell-ringing with multiple voices speaking different languages. While it resisted being a coherent movement, Dada articulated a clear sense of social resistance, demonstrating some of the ways art could operate as anti-art, challenging contemporary artistic and social conventions. Dadaists’ performances were characterised by apparent nonsense and freedom, fantasy, chance, spontaneity, and anarchic play and Dada aimed deliberately to challenge and provoke audiences. The name ‘dada’ itself has different meanings in different languages, an ambiguity Dada cultivated. Its practice spread across Europe with the publication of Dada magazines, books and posters, and the foundation of dedicated gallery spaces. This led to a split among its primary exponents, who argued for and against Dada’s institutionalization.

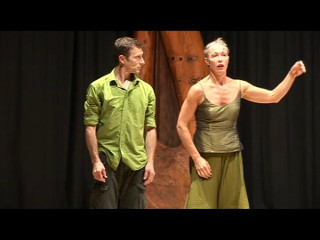

Despite Dada’s relative brevity as a movement, its influence has been enormous. Dada’s expressive principles for example, worked their way into the choreography of Rudolf von Laban and Mary Wigman, who attended the Cabaret Voltaire, and its collage composition extended later into the epic style developed by Erwin Piscator and Bertold Brecht. Dada’s anti-naturalistic avant-gardism and its experiments with chance were later extended in music by John Cage and in dance by choreographers including Pina Bausch. From the RCTP